Difference between revisions of "OOXML/Open Packaging Conventions (OPC)"

PeterKelly (Talk | contribs) (Add diagram) |

PeterKelly (Talk | contribs) m (Spelling/grammar) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Like ODF, OOXML documents are ''containers'', stored physically as zip archives. Most of the files in the archive are in XML format, though binary files may be included in specific cases (e.g. for images). | Like ODF, OOXML documents are ''containers'', stored physically as zip archives. Most of the files in the archive are in XML format, though binary files may be included in specific cases (e.g. for images). | ||

| − | Each OOXML document has certain files that serve a particular role, such as the document content, stylesheet, | + | Each OOXML document has certain files that serve a particular role, such as the document content, stylesheet, metadata, and so forth. However, instead of simply using fixed path names within the archive (as ODF does), a part of the OOXML specification called '''Open Packaging Conventions (OPC)''' defines an additional layer of abstraction on top of the zip directory, which must be consulted to determine the actual paths at which certain files can be found. |

== Root relationships == | == Root relationships == | ||

| − | Each file inside an OPC package is called a | + | Each file inside an OPC package is called a '''part''', and these are arrange as a directed graph - similar, but theoretically more flexible than a traditional directory tree. The graph's vertices are parts (files), and edges are relationships. The set of outward relationships for a given part is stored as XML, in a file whose name is derived from the filename of the part. |

| − | To give a concrete example, let's consider the case of an empty document created in Word 2011 for | + | To give a concrete example, let's consider the case of an empty document created in Word 2011 for Mac. This document has the following package structure, where each box (except for the root) represents a part: |

[[File:OOXML_OPC_Example.svg]] | [[File:OOXML_OPC_Example.svg]] | ||

| − | The XML file containing the relationships for a given part is located in <tt>_rels/(filename).rels</tt>, relative to the directory containing that file. For the root relationships, this is simply <tt>/_rels/.rels</tt>. For another file, say <tt>/word/document.xml</tt>, the path is <tt>/word/_rels/document.xml.rels</tt>. Let's have a look at the root relationships file: | + | The XML file containing the relationships for a given part is located in <tt>_rels/(filename).rels</tt>, relative to the directory containing that file. For the root relationships, this is simply <tt>/_rels/.rels</tt>. For another file, say <tt>/word/document.xml</tt>, the path is <tt>/word/_rels/document.xml.rels</tt>. |

| + | |||

| + | Let's have a look at the root relationships file: | ||

<source lang="xml"> | <source lang="xml"> | ||

| Line 35: | Line 37: | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

| − | As you can see from the file, each relationship has an id, a type, and a target. The target is simply the filename of the part; this is relative to the location of the source of the relationship (in this case, the root directory). The type indicates what the format or purpose of that part is. The id serves as a unique identifier to distinguish one relationship from another. | + | As you can see from the file, each relationship has an '''id''', a '''type''', and a '''target'''. The target is simply the filename of the part; this is relative to the location of the source of the relationship (in this case, the root directory). The type indicates what the format or purpose of that part is. The id serves as a unique identifier to distinguish one relationship from another. |

| − | In some cases, you need to look up a relationship based on it's type | + | In some cases, you need to look up a relationship based on it's type. For example, to determine the name of the file containing the content of a word document, you would need to look through the relationships file to find one that has the appropriate namespace. In other cases, you would use the id. For example, where an image is included in a document, it is referenced by its relationship id (in the document part's relationships, not the root), and that id can then be used to find the path of the image. |

== Part relationships == | == Part relationships == | ||

| − | Let's now have a look at the relationships file for the document content part. We know that in this particular | + | Let's now have a look at the relationships file for the document content part. We know from above that in this particular package the filename happens to be <tt>word/document.xml</tt>, so we can infer that its relationships must be stored in <tt>word/_rels/document.xml.rels</tt>. Note that if a given part does not have any outgoing relationships, it does not need to have a relationships file. |

<source lang="xml"> | <source lang="xml"> | ||

| Line 74: | Line 76: | ||

As you can see, this file is very similar to the root relationships file; the main difference is that it has a different set of relationships. The most important thing to note here is that all <tt>Target</tt> values are relative to the directory containing the source part's file. In this case, the file is <tt>/word/document.xml</tt>, so the styles part is located at <tt>/word/styles.xml</tt>, and the theme part is located at <tt>/word/theme/theme1.xml</tt>. | As you can see, this file is very similar to the root relationships file; the main difference is that it has a different set of relationships. The most important thing to note here is that all <tt>Target</tt> values are relative to the directory containing the source part's file. In this case, the file is <tt>/word/document.xml</tt>, so the styles part is located at <tt>/word/styles.xml</tt>, and the theme part is located at <tt>/word/theme/theme1.xml</tt>. | ||

| − | Just as when determining the filename of the document content part, you must always look at the relationships file to determine the location of other related parts, such as the styles | + | Just as when determining the filename of the document content part, you must always look at the relationships file to determine the location of other related parts, such as the styles. Although MS Word seems to always use these particular paths, it's not guaranteed by the specification, and in theory there could be some other application which uses a completely different set of physical path names instead. As long as you look up relationships based on the required type, you'll always find the correct physical path. |

== External relationships == | == External relationships == | ||

| − | So far, all of the relationships we've seen are to other files in the same package. However, it is also possible to have ''external'' | + | So far, all of the relationships we've seen are to other files in the same package. However, it is also possible to have ''external'' relationships, for example when hyperlinks are included in a document. [[WordProcessingML]] does not directly include URLs for hyperlinks, but instead stores a relationship for the link, which the content document refers to by its relationship id. |

Here's an excerpt of a WordProcessingML file containing a hyperlink to http://www.openoffice.org | Here's an excerpt of a WordProcessingML file containing a hyperlink to http://www.openoffice.org | ||

| Line 107: | Line 109: | ||

Note the <tt>TargetMode</tt> attribute here, which was not set in any relationships shown earlier. Every relationship has a target mode; the default value is <tt>Internal</tt>. Here, it is explicitly set to <tt>External</tt>, so that we know it's not referring to another file in the package. | Note the <tt>TargetMode</tt> attribute here, which was not set in any relationships shown earlier. Every relationship has a target mode; the default value is <tt>Internal</tt>. Here, it is explicitly set to <tt>External</tt>, so that we know it's not referring to another file in the package. | ||

| − | The | + | The <tt>Type</tt> of this relationship might initially seem sufficient to determine that the link is external, and this would be true if you had a list of all types that were meant to refer to external resources. However, it is possible that a piece of code that deals with OPC packages (such as a validation algorithm) may not have this information, and without knowing the target mode, might look for a file named <tt>http://www.openoffice.org</tt>, not find it, and report an error. Thus the <tt>TargetMode</tt> attribute allows for arbitrary types (including any added to future versions of the spec, or proprietary extensions) to be used for relationships, while still allowing a program examining the package to check that all internal references are valid. |

Revision as of 18:32, 23 July 2014

Like ODF, OOXML documents are containers, stored physically as zip archives. Most of the files in the archive are in XML format, though binary files may be included in specific cases (e.g. for images).

Each OOXML document has certain files that serve a particular role, such as the document content, stylesheet, metadata, and so forth. However, instead of simply using fixed path names within the archive (as ODF does), a part of the OOXML specification called Open Packaging Conventions (OPC) defines an additional layer of abstraction on top of the zip directory, which must be consulted to determine the actual paths at which certain files can be found.

Root relationships

Each file inside an OPC package is called a part, and these are arrange as a directed graph - similar, but theoretically more flexible than a traditional directory tree. The graph's vertices are parts (files), and edges are relationships. The set of outward relationships for a given part is stored as XML, in a file whose name is derived from the filename of the part.

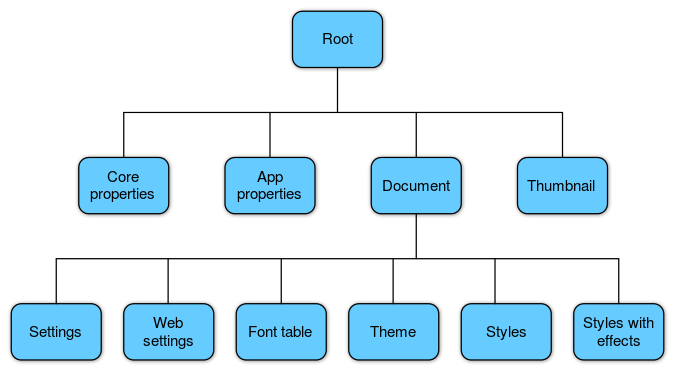

To give a concrete example, let's consider the case of an empty document created in Word 2011 for Mac. This document has the following package structure, where each box (except for the root) represents a part:

The XML file containing the relationships for a given part is located in _rels/(filename).rels, relative to the directory containing that file. For the root relationships, this is simply /_rels/.rels. For another file, say /word/document.xml, the path is /word/_rels/document.xml.rels.

Let's have a look at the root relationships file:

<Relationships xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships"> <Relationship Id="rId3" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships/metadata/core-properties" Target="docProps/core.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId4" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/extended-properties" Target="docProps/app.xml"/ <Relationship Id="rId1" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/officeDocument" Target="word/document.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId2" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships/metadata/thumbnail" Target="docProps/thumbnail.jpeg"/> </Relationships>

As you can see from the file, each relationship has an id, a type, and a target. The target is simply the filename of the part; this is relative to the location of the source of the relationship (in this case, the root directory). The type indicates what the format or purpose of that part is. The id serves as a unique identifier to distinguish one relationship from another.

In some cases, you need to look up a relationship based on it's type. For example, to determine the name of the file containing the content of a word document, you would need to look through the relationships file to find one that has the appropriate namespace. In other cases, you would use the id. For example, where an image is included in a document, it is referenced by its relationship id (in the document part's relationships, not the root), and that id can then be used to find the path of the image.

Part relationships

Let's now have a look at the relationships file for the document content part. We know from above that in this particular package the filename happens to be word/document.xml, so we can infer that its relationships must be stored in word/_rels/document.xml.rels. Note that if a given part does not have any outgoing relationships, it does not need to have a relationships file.

<Relationships xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships"> <Relationship Id="rId3" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/settings" Target="settings.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId4" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/webSettings" Target="webSettings.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId5" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/fontTable" Target="fontTable.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId6" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/theme" Target="theme/theme1.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId1" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/styles" Target="styles.xml"/> <Relationship Id="rId2" Type="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/2007/relationships/stylesWithEffects" Target="stylesWithEffects.xml"/> </Relationships>

As you can see, this file is very similar to the root relationships file; the main difference is that it has a different set of relationships. The most important thing to note here is that all Target values are relative to the directory containing the source part's file. In this case, the file is /word/document.xml, so the styles part is located at /word/styles.xml, and the theme part is located at /word/theme/theme1.xml.

Just as when determining the filename of the document content part, you must always look at the relationships file to determine the location of other related parts, such as the styles. Although MS Word seems to always use these particular paths, it's not guaranteed by the specification, and in theory there could be some other application which uses a completely different set of physical path names instead. As long as you look up relationships based on the required type, you'll always find the correct physical path.

External relationships

So far, all of the relationships we've seen are to other files in the same package. However, it is also possible to have external relationships, for example when hyperlinks are included in a document. WordProcessingML does not directly include URLs for hyperlinks, but instead stores a relationship for the link, which the content document refers to by its relationship id.

Here's an excerpt of a WordProcessingML file containing a hyperlink to http://www.openoffice.org

<w:p> <w:hyperlink r:id="rId5"> <w:r> <w:rPr> <w:rStyle w:val="Hyperlink"/> </w:rPr> <w:t>Open Office</w:t> </w:r> </w:hyperlink> </w:p>

Here, we can see that the hyperlink refers to relationship id "rId5". If we look in the relationships file for the content part, we'll see the following:

<Relationship Id="rId5" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/hyperlink" Target="http://www.openoffice.org" TargetMode="External"/>

Note the TargetMode attribute here, which was not set in any relationships shown earlier. Every relationship has a target mode; the default value is Internal. Here, it is explicitly set to External, so that we know it's not referring to another file in the package.

The Type of this relationship might initially seem sufficient to determine that the link is external, and this would be true if you had a list of all types that were meant to refer to external resources. However, it is possible that a piece of code that deals with OPC packages (such as a validation algorithm) may not have this information, and without knowing the target mode, might look for a file named http://www.openoffice.org, not find it, and report an error. Thus the TargetMode attribute allows for arbitrary types (including any added to future versions of the spec, or proprietary extensions) to be used for relationships, while still allowing a program examining the package to check that all internal references are valid.